Responsible Science Communication re: Digital Media by Aparna Nadig

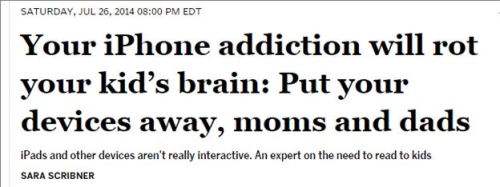

Many academics are much more comfortable communicating their research findings to other academics than to the popular press, and regard the sound bites and snippets of research served up in the press with scorn. Yet, the intersection between research and the popular press is critical and particularly consequential when it comes to topics of health and education, as for our topic of digital media for young children. Our second Round Table Discussion focused on the Responsible Science Communication re: Digital Media to move past this passive position and consider what is needed to achieve more evidence-based and responsible dissemination of research findings. We started by exploring the context created by the popular press on digital media use by children, as this is the environment that educators and professionals working with children, digital media professionals, and scientists confront when trying to convey key messages about digital media use. I asked participants (who self-identified as students or researchers, 40%, education or health professionals, 32%, parents of young children, 16%, digital media professionals, 8%, or other 4%) to report their gut response with respect to how much they agreed with a barrage of headlines, from sensational takes like this one (1) from Salon.com which talks about “rotting kids brains”:

(1)

This is the report from the audience on the Salon headline:

To more balanced and nuanced reporting as seen in this article (2) from BBC News, which discusses varying degrees of video gaming being related to different outcomes in children:

(2)

http://www.bbc.com/news/health-28602887

Polling results showed that our participants, who were well-informed about digital media use and/or how to communicate with families of young children, largely disagreed with the sensationalist headline and fear-mongering approach of article (1), and conversely were much more in agreement with the nuanced headline of (2) which appeared give a more comprehensive view of a research study.

Unfortunately, in our search of news headlines on digital media use in children we overwhelmingly encountered the inflammatory approach seen in example (1).

We then worked through a detailed example of the disconnect between popular press stories (using an example article from The Telegraph, 3 below) and research evidence, leading to inflammatory and potentially dangerously misleading claims.

Participants discussed the causes and impacts of such claims on different stakeholder groups, as well as what should be done to improve the accuracy and reliability of reporting. Recommendations to increase the public’s understanding of research evidence on digital media included:

Taking an active role in critical dissemination of research findings

-

- Sharing information within our social networks, debunking misinformation

- Establishing an internet presence on blogs and social media. Blogs can serve as a more detailed information source for journalists, and can be used by journalists to complement press releases if they cannot reach scientists: http://www.theguardian.com/science/blog/2012/mar/07/scientists-help-improve-science-journalism

- Task members of the research team (RAs, graduate students) to comment on articles, online forms to voice other perspectives

- Making use of outreach through teacher blogs for parents of school children

Scientists taking steps to be more savvy communicators of their research evidence

- Cherry pick your journalists and media outlets to control your message

- Be prepared, have your key messages ready for sound bites

- Nip exaggerated claims in the bud, remove them from academic press releases. University press releases, not journalists, are often the original source of overstated claims (Sumner et al., 2014 BMJ; http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g7015)

- Be able to communicate findings clearly in lay language, convey consistent, simple messages

- Publish using open access methods to increase availability of full research reports

- Engaging in discussion and efforts with journalists to address this disconnect (e.g., as in this debate with journalists and scientists, hosted by the Royal Institution, UK in 2012, http://richannel.org/alok-jha-science-and-the-media–presentations)

Making use of media mediators

- Join The Conversation, an organization and website committed to knowledge-based journalism. Academics and researchers work with journalists to provide evidence-based, ethical and responsible information. (The UK & Australia lead on this, there is a US pilot version: https://theconversation.com/us)

- Use filters, like moms with apps, to locate good content. Moms with apps supports the thoughtful use of technology, and originated from a group of parents and family-friendly app developers: http://blog.momswithapps.com/

- Researchers can gain from involving their institutional Public Relations or Communications offices in dissemination efforts

- Consider branding and developing a type of science marketing where communications experts are involved in research teams

Widespread changes needed to have a more critical public in the digital age

- The ability to extract and evaluate the validity of information should be emphasized in school curriculums

- Basic literacy in how to be discerning and critically evaluate claims

- Make the public aware that universities and their websites are great, valid tools to access relevant information

The topic of this Round Table discussion was a novel one for me in my history of attending research conferences, and the response of many of our participants indicated that it was similarly new to them and that they found it important and refreshing to consider this intersection of research and the press. The general take home message was one urging researchers, educators and professionals working with young children to get up and take an active role in the responsible communication of information on digital media use in children, in their communities as well as in online forums.

[…] #DigLitMcGill Conference Day 2 Theme II Report […]

[…] most common attitude to digital media that is projected in the public sphere at present is one of moral panic, especially with regard to digital media use by children. However, […]